Antigua Guatemala Today

La Antigua Guatemala is among the best preserved colonial cities in the world. It is a charming and magical little town that transports visitors about 300 years in history. It was once the third largest Spanish colony in the Americas and more than 30 monastic orders built their impressive monasteries, convents, and cathedrals in the city.

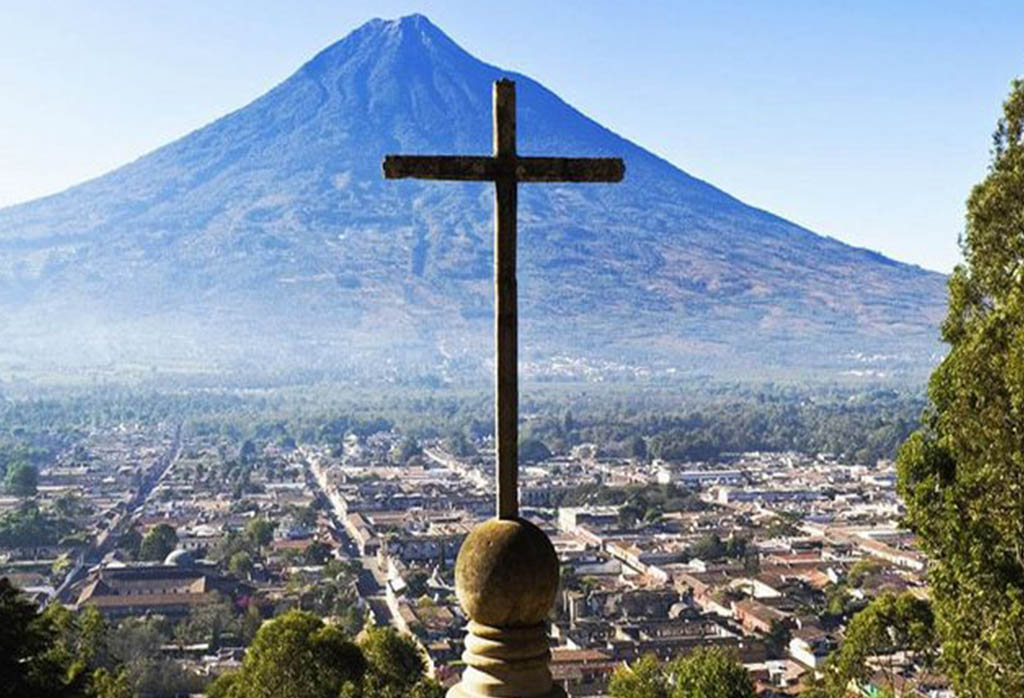

From colonial architecture to beautiful scenery – with stunning views of the Agua, Fuego, and Acatenango volcanoes – La Antigua combines colonial history with a variety of cultural activities including art galleries, exhibitions, performing arts, movies, forums and tourism.

La Antigua hosts the largest celebrations of Lent and Easter in the Western Hemisphere, to which many are drawn by religious fervor and by the beautiful carpets of sawdust and flowers that are made along the processional routes.

History of Antigua Guatemala:

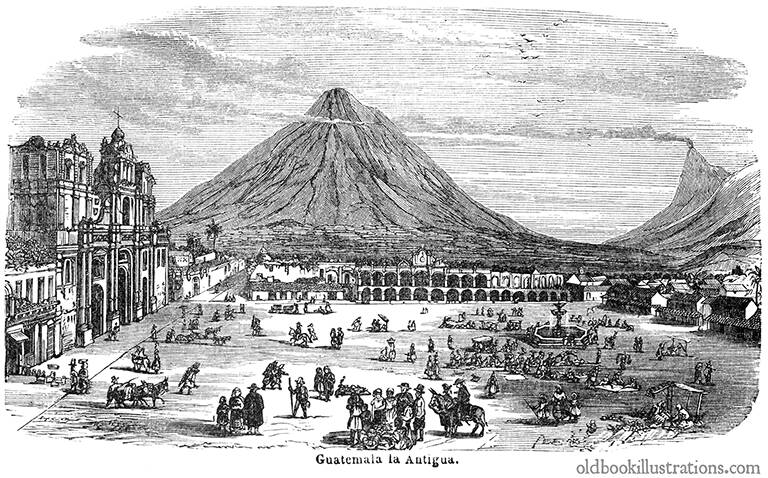

Founded in 1543, was the seat of Spanish colonial government for the Kingdom of Guatemala, which included Chiapas (southern Mexico), Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The full title bestowed upon the city was Muy Leal y Muy Noble Ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros de Goathemala, that is, the “Very Loyal and Very Noble City of Saint James of the Knights of Guatemala.” For the first century or more of its existence the city did not live up to the pretentious official title, but it ultimately grew into the most important city in Central America, filled with monumental buildings of ornate Spanish colonial architecture. By 1773, in addition to the cathedral and government palace the city could boast of over 30 churches, 18 convents and monasteries, 15 hermitages, 10 chapels, the University of San Carlos, five hospitals, an orphanage, fountains and parks, and municipal water and sewer systems. According to many authors, Antigua Guatemala in its heyday, with a population of perhaps 60,000, was surpassed in the New World only by Mexico City and Lima.

Throughout its history the city now known as Antigua Guatemala, or La Antigua, was repeatedly damaged by earthquakes, and always the Antigueños rebuilt, bigger and better. But on July 29, 1773, the day of Santa Marta, earthquakes wrought such destruction that officials petitioned the King of Spain to allow them to move the capital to safer ground, which led to the founding in 1776 of present-day Guatemala City.

Antigua was left to rusticate, largely but never completely abandoned. Today its monumental bougainvillea-draped ruins, and its preserved and carefully restored Spanish colonial public buildings and private mansions give form to a city of charm and romance unequaled in the Americas. In 1979 UNESCO recognized Antigua Guatemala as a Cultural Heritage of Mankind site.

For more than two centuries, the seat of Spanish colonial government was the Palace of the Captains-General. Construction was begun on the original building in 1549 and completed in 1558, but the building has been repeatedly reconstructed and altered following damaging earthquakes. In 1735 the Casa de la Moneda (mint) was inaugurated in this large complex. But most of the structure was destroyed in the 1773 quakes that brought the city to its knees. Today the beautiful two-tiered arched façade has been restored, and the building houses government, city police, and INGUAT (Guatemala Tourist Institute) offices, but the present palace is but a small remnant of the former complex. The palacio was yet again heavily damaged in the Feb. 4, 1976 earthquake.

On the east side of the Plaza de Armas stood the great Catedral, inaugurated on Nov. 5, 1680, after eleven years of construction. This huge building replaced an earlier cathedral begun in 1542 and worked on intermittently for many decades. Various notables from the Conquest were buried here: Bernal Diaz del Castillo, conquistador and author of The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico, lived out his latter days in Antigua and was buried in the original cathedral; the remains of the Don Pedro de Alvarado, the conqueror of Guatemala, were brought here in 1568 for re-interment.

The 1680 cathedral was laid out with three aisles and salient transepts in a cruciform plan. Bays off the side aisles contained chapels. This church was the largest and most lavishly furnished in Central America. The bishop’s palace was built along the north side of the cathedral and connected to it. In 1717 the structure was badly damaged by earthquakes, but was rebuilt. In 1743 it was raised to the rank of a metropolitan cathedral and became the seat of the archbishop. In 1773 it succumbed to the Santa Marta earthquakes.

The present day church is a reconstruction of a small portion –only as far back as the first two bays– of the front of the cathedral. This reconstruction was completed in the 1820s, when the cathedral was converted into a parish church. The present façade differs only in minor ways from that shown in a 1784 sketch of the cathedral, and the lower story is very likely much as it was when first completed in 1680.

The gloomy but impressive ruins of the giant nave can be entered today from the south portal, and are well worth the modest admission charge.In the center of the Plaza de Armas stands this famous fountain. Designed in 1739 by Miguel Porras, one of the city’s renowned colonial architects, the Fuente de las Sirenas (Fountain of the Sirens) is one of many gracing Antigua’s principal plazas and courtyards. These fountains were more than just ornamental. Although piped water reached important buildings and dwellings in the seventeenth century, fountains served as water supplies for humble dwellings, even into the present century.On the north side of the Plaza de Armas, facing the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales stands the Ayuntamiento or city hall, dating from 1743, and replacing an earlier, less imposing structure. Remarkably enough, this building was little damaged by the 1773 earthquakes. Today it houses two museums, the Museo de Santiago and the Museo del Libro Antiguo. The latter museum, the Museum of Old Books, is located in the main portal to the Ayuntamiento, the site of a printing press established in 1660. Until a few years ago these bronze cannon barrels lay unattended under the arcade of the Ayuntamiento, mute testimony to Spanish colonial power.Just off the southeast corner of the Plaza de Armas, across the street from the entrance to the ruins of the Catedral is the entry to Universidad de San Carlos, built around 1763, when the university, founded in 1676, was moved to this site. The building apparently survived the 1773 earthquake in relatively good condition, but by the end of the 18th century required extensive renovations. The present portal was built in 1832 when the building was turned into a public school, the university having been moved to Guatemala City where it remains today. The interior of the old university building features a fine courtyard with a fountain surrounded by Moorish arches. Its many repairs and renovations notwithstanding, the colonial architecture has been faithfully retained and this building is one of the most beautiful and intact examples in Antigua. Today it houses the Museo de Arte Colonial, or Museum of Colonial Art.

One of the most fascinating colonial sites in Antigua is Las Capuchinas, the Capuchin Convent, completed in 1736 under the direction of the chief architect of the city, Diego de Porres. Today the convent is partially intact and partially in ruins. The intact portions house a museum and offices for the National Council for the Protection of Antigua Guatemala. The ruined sections include baths for the nuns, and an unusual circular area containing novices cells, each complete with it own privy. Below this circular patio is a mysterious, subterranean chamber that resonates wonderfully on certain notes; no one seems to know the original purpose of this dungeon-like chamber. The ruined nave of the chapel, approximately 120 feet long, can be viewed from the nuns’ choir loft, accessed from the second floor level of the ruins. From the second floor a great view can be had of the twin volcanoes Fuego (left, puffing steam in this photo) and Acatenango (right, with a puff of Fuego’s steam drifting over it).

The peculiar stubby tower here is a chimney, for the refectory kitchen on the ground floor. Such chimneys are known as linternas due to their resemblance to an old-fashioned candle lantern. Looking across the ruins, one sees the towers of La Merced church.The Mercedarian order was established in Guatemala in 1538, and the order had built a church in Antigua by 1546. This church was destroyed by earthquakes in 1565, but subsequently rebuilt, only to be ruined again in the earthquakes of 1717. The present church of La Merced was finished in 1767, just six years before the Santa Marta quakes that led to the abandonment of Antigua as the capital. The façade is one of the most beautiful in Antigua, featuring intricate and ornate patterns in white stucco on a yellow background. The church is also a good example of the “earthquake baroque” architectural style popular by necessity in Central America: short squatty bell towers, in contrast to the soaring towers of the churches built in seismically less active Mexico during the same epoch. Although somewhat damaged in 1773, the church was repaired and remains in service today, but the original gilded altars and other fine furnishings were removed to the new Mercedarian church in Guatemala City when the order moved to the new capital.The monastery attached to La Merced was totally destroyed by the Santa Marta quakes, and never rebuilt. Within the ruined cloister stands enormous Fuente de Pescados (Fountain of the Fish), reputedly named for the fish-breeding experiments done there by the Mercedarian brothers. This is largest of Antigua’s many fountains, with a diameter of over 80 feet.

Las Merced Church Antigua Guatemala La Merced is the starting and ending point for the famous Good Friday procession of Antigua. The procession involves a cast of many thousands, including Roman centurions and cavalry, self-flagellating penitentes, Pontius Pilate, the two thieves, statues of saints and of Christ in various stages along the Via Dolorosa, high Catholic officials with attendants swinging censers, brass bands playing unimaginably dolorous funereal marches, and, of course, statues of the Virgin Mary (these borne by women). The procession requires eight hours to pass through Antigua’s streets, which are emblazoned with alfombras (carpets) of pine needles, flowers and brightly dyed sawdust laid in designs. The climax at any one viewing point is when the gigantic, multi-ton (float) of Christ carrying the cross, lumbers by swaying from side to side as the 80 bearers step in unison, promoting the illusion that the statue is actually walking. Eventually this great pageant winds its way back to La Merced where in a scene worthy of Cecil B. DeMille, Christ is turned about, then backed into the church to repose until next year’s Semana Santa (Holy Week).

Another very special ruin is that of the convent of Santa Clara founded in 1699 by the arrival of five nuns and one legate from Mexico. The convent’s first church was completed in 1705, but destroyed in 1717. The remains standing today are those of a new church and convent started in 1723 and finished in 1734. The ruined nave and altar were constructed over gloomy subterranean vaults that are best explored with a flashlight. A complex of corridors and stairwells gives access to various parts of the shadowy ruin. But the greatest beauty of Santa Clara is its ruined cloister, featuring a two-tiered arcade of nine half-circle arches on all four sides.

Outside the church and cloister, the remains of the Santa Clara convent are less imposing, but include the linterna, still heavy with smoke inside, that marks the site of the former cocina (kitchen). The low arch is a feature found in many of the colonial kitchens: the ovens and grills were located directly under the chimney, and the low arch helped keep the smoke going up the chimney rather than into the remainder of the food preparation area which was high ceilinged.

The church of El Carmen, completed in 1728, is the third to occupy this site. The main façade of the church is ornate baroque, and unique in Antigua with its triple pairs of columns set on podia projecting forward from the main wall in place of the niches and saints usually occurring here on Antigua’s churches. Adjoining the church in the space now occupied by the red-painted private home were the conventual buildings. It was here that the Capuchin nuns were first housed upon their arrival in Antigua in 1726, prior to the building of Las Capuchinas. Today none of the convent buildings remain, only the the ruined church is still standing. The interior of the nave was just under 150 feet long.

Religious and government buildings do not hold a monopoly on Spanish colonial architecture in Antigua. The palacial homes of wealthy Spaniards and creoles, some taking up a good portion of a city block, are scattered through the town, but views of those in private hands may be restricted to the long whitewashed walls that face the cobbled streets. Others, such as the Casa de los Leones have been converted into hotels and are open to the public. The Casa de los Leones, named for the sculptured stone lions rampant flanking the main portal, was built before the 1717 earthquakes. As is typical of the better colonial homes, rooms are arranged around patios. Today the Casa de los Leones has been modified to serve as a hotel, La Posada de don Rodrigo, preserving some original colonial furnishings such as the heavy wooden shutters and doors. A characteristic element of colonial architecture is the corner window, which here opens into the bar of the Posada de don Rodrigo.

A private home that is open to the public on specified hours is the Casa Popenoe, originally constructed in the first half of the 17th century for don Luís de las Infantas y Mendoza, a Spaniard and judge in the Royal Audiencia. This house had fallen into ruins and was lovingly restored by Dr. Wilson Popenoe and his wife Dorothy in the 1930s. The Popenoes furnished the house with period antiques collected over the years. Like many colonial residences, the home is built right up to the sidewalk and presents massive walls to the public. But the interior is graced with flowered patios flanked by cool shaded corridors. Popenoe’s collection of colonial art and furnishings, the complete colonial kitchen, baths and laundry areas, dovecote and other features of this home make it a must to the visitor interested in how the Spanish colonial elite lived. Dr. Popenoe was an American agronomist who worked in Central America for many years; the story of the restoration of this wonderful home was the subject of a book by Louis Adamic, “The House in Antigua”.

Colonial architecture and modern construction in colonial style is found throughout Antigua in mansions and in humbler homes. Wandering along the cobbled streets one passes by numerous portones, typically heavy wooden double doors studded with large brass or iron bosses. The double doors could be opened simultaneously to permit the passage of a horse and rider or a carriage, or individually to allow entry and exit of people afoot. In very large portals a smaller door built as a panel into one of the pair of large doors opens for foot traffic. Some buildings featured corner posts of stone matching the stonework of their portals; these corner posts served a decorative purpose while at the same time protecting the building from damage when struck by passing carts or carriages.

The walls of colonial homes were built thick, partly in the vain hope of surviving earthquakes, and accordingly window openings must be deep, giving the opportunity for artistic expression in deeply molded fenestration. More commonly windows have a wide flat sill with ample room to sit on, as seen here in the window to the left of the deeply recessed and molded window. Corner windows form especially pleasant and secluded retreats from which aristocratic gentlewomen might observe passers-by. Virtually all windows are barred with either wrought iron or wooden grills.Although the abandonment of Antigua as the seat of colonial government also entailed the transferral of its church institutions and its wealthy families to new homes in the new capital, Antigua was never totally depopulated. Poorer people stayed behind in the ruined city. Massive church and convent ruins became homes and places of business. In fact, until the 1976 earthquake the huge ruins of the church and convent of the Compañía de Jesús served as the municipal marketplace. In 1779 Antigua, reclassified (demoted) as a villa, was designated the capital of the province of Sacatepéquez.

Antigua grew slowly through the 19th century, during which period some restoration work was done on the former cathedral, now serving as a parish church. But it was not until the mid-20th century that the historic and architectural value of the colonial buildings and ruins began to be appreciated. In 1944 the Government of Guatemala, under Jorge Ubico, declared Antigua Guatemala a National Monument, giving formal recognition to the site as a unique part of Guatemala’s historic and cultural patrimony. In 1965 the Pan American Institute of Geography and History named Antigua the “Monumental City of the Americas”. Four years later the Consejo Nacional para la Protección de Antigua Guatemala was established. Today this Council oversees restoration work and sets guidelines for new construction work in Antigua, with the goal of preserving the colonial ambience and integrity of the city. Finally, as mentioned earlier, the city was designated a Cultural Heritage of Mankind site by UNESCO in 1979, further emphasizing the uniqueness of the preserved colonial architecture and the cultural value of Antigua’s great beauty to all the world’s people.